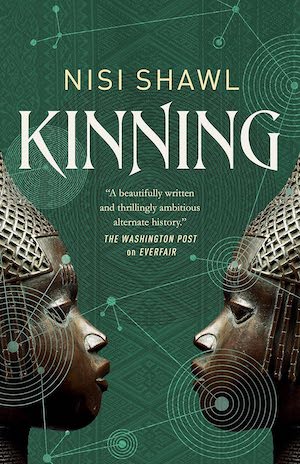

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Kinning, the sequel to Nisi Shawl’s alternate history debut Everfair, out from Tor Books on January 23.

Tink and his sister Bee-Lung are traveling the world via aircanoe, spreading the spores of a mysterious empathy-generating fungus. Through these spores, they seek to build bonds between people and help spread revolutionary sentiments of socialism and equality—the very ideals that led to Everfair’s founding.

Meanwhile, Everfair’s Princess Mwadi and Prince Ilunga return home from a sojourn in Egypt to vie for their country’s rule following the abdication of their father King Mwenda. But their mother, Queen Josina, manipulates them both from behind the scenes, while also pitting Europe’s influenza-weakened political powers against one another as these countries fight to regain control of their rebellious colonies.

Will Everfair continue to serve as a symbol of hope, freedom, and equality to anticolonial movements around the world, or will it fall to forces inside and out?

CHAPTER ZERO

June 1916

Kisangani, Everfair

Princess Mwadi knelt in the jasmine’s warm shade. Both Sifa and Lembe slept. That had never before happened, but the eyelids of both her mother’s women stayed shut when Mwadi whispered their names. And Lembe snored, though lightly. And Sifa smacked her lips, which she would never have done in Mwadi’s presence while awake.

Daring discovery, the princess stood, still lapped in the vines’ deep green shadows. Her brother Ilunga lay within the palace walls, recuperating from the new illness under the care of Yoka, one of their father’s most trusted and discreet counselors, and visited frequently by King Mwenda himself; her mother, Queen Josina, had established rooftop gardens to house the hives of her holy bees upon her return from her diplomatic mission to Angola, and there she was to be found most days. Though ostensibly the queen dwelt here in the palace courtyard with the other royal wives and daughters, Mwadi had quickly learnt how to amuse herself without expectation of her mother’s praise or censure. And also how to seek out and enjoy her mother’s company without being shooed away from the secrets Queen Josina liked to gather.

How, as Miss Rima Bailey would have put it, to sneak around.

The trick was to become something else. No longer content as a velvet-faced, sturdy-armed thirteen-year-old girl, Princess Mwadi concentrated on her resemblance to the sighing rain, then slipped free of the pavilion’s overhanging roof to join the rain’s fall.

Languorous in the midday’s moist heat, ranks thinned by the ravaging new illness, the palace guard proved no impediment to Mwadi’s departure. And Kisangani’s thoroughfares led her where she wanted to go so easily—the dwindling waters between built-up roads coming no higher than her knees, so that she might wade unmolested the whole way.

Buy the Book

Kinning

The city had grown since her father first established his court here, back before she or Prince Ilunga had been born. And it had grown even more in the two years since she acted the role of Bo-La alongside Miss Rima in Sir Matty’s play. The atolo tree planted near the shelter of the king’s ancestors stood surrounded now by many similar shelters sharing the tree’s protection. So broad its branches, by itself the tree darkened almost all the sacred precinct’s ground. So high its crown, the misting rain wreathed around its leaves like dagga smoke. So snaking its roots, she had to stoop to the soil and feel her way among them with her hands. So fat and slick the trunk, she didn’t even try to climb it, merely clasped it to her, breathing in its clean, wild scent.

She had reached her goal! She threw back her head in joy and saw it—the king’s original ceremonial shongo, yes! The green of its copper was duller and bluer, the curves of its blades were fuller and longer, than the intervening foliage.

So high above her head… impossible to touch it. It had stayed lodged in the gleaming brown bark higher than the ceiling of the palace pavilion for more than forty seasons—ever since her father hurled it there and decreed that whoever drew it free would rule after him. Warning stories told of the injuries borne by pretenders to Everfair’s throne in their pursuit of this prize: multiple bones broken in sudden, inexplicable falls; crippling wounds gouged in their flesh by the beaks of invisible crows. But from the overheard conversations of her mother’s rivals, the princess knew for certain that once she released the shongo from its resting place she could call herself her father’s heir, as these women’s sons had attempted to do. As her stupid brother Ilunga had tried to do as well. She had to retrieve it for herself, successfully—but how?

Arching her back, she continued gazing upward. A limb emerged from the tree’s main body to the shongo’s right, and just a little lower. Thinning gradually, gracefully, the long limb drooped near its end—Mwadi whirled to check—low enough! Or nearly so; she picked her way to where it waved almost, almost within her grasp. A glance around: no one was present. As she had planned. Offerings would be made later, at the time of the evening meal. Nobody had been here when she arrived, and nobody had arrived since.

With practiced swiftness she unwound her headwrap—a wider strap than babies wore, as Mwadi was soon to be a woman. A couple of tosses and it went over the limb. First she dragged the limb down. When the wood no longer bowed to her weight she paused to make sure again she was alone, then jumped! Still hanging by the loop of her headwrap she swung her legs high and locked ankles around the lowered limb. Of course it held her. Creeping along its underside like a caterpillar—bunch, stretch, bunch, stretch—she moved toward the tree’s center. Once there it was a struggle, but she got herself upright and facing in. No dizziness or loss of grip or balance. No plunge from this hard-won height. No flock of ghosts.

Now. Bracing herself by tightening her thighs she leaned left, took the wooden haft of the king’s shongo in both hands, and tugged. It came free slowly, like a well-watered cassava plant.

Triumph! Everfair was hers! Entranced by her happy prospects she sighed and stroked the glowing, newly naked blade, largest of the shongo’s three. Burial in the atolo tree’s flesh had kept it shining bright. As bright as the future reign of Queen Mwadi.

Now to tell King Mwenda, so he could make the succession official. And to share the news of her good fortune with her mother, his favorite. And to gloat openly, in his face, upon her victory over Ilunga.

No, she would be kinder to him than that. Appoint him minister of something. He was her brother, after all, by both father and mother.

Surely that mattered.

According to Queen Josina, every relationship entered into mattered. Each was of the utmost importance. Slowly, thoughtfully, Mwadi came down off of the atolo limb and untied her headwrap. She wound it around and around the shongo’s shaft, pulling it tight, then laid it loosely over the sharp-forged cutting edges.

Her mother shared wisdom like it was chocolate, always possessed of a personal supply from which she doled out small bits, seemingly on a whim. Mwadi had learned as a child to savor her mother’s pronouncements, to chew them over and extract their constantly changing, ever-refreshing truths.

As the princess left the grove surrounding the atolo for the ramp leading down to the partially flooded thoroughfare, she frowned at the ground on which she walked. She was going to reign over this land—over this earth, over the very soil clinging to her bared feet. Was that a relationship? Even now, at this point, before she actually ascended to Everfair’s throne? Or perhaps not even then. Perhaps only relationships with living entities should be counted? The trees, then? A low branch brushed the top of her head as she stepped onto the ramp’s gravel, as if in a tender farewell.

The peak of the day had passed, and Mwadi met a few others on her way home to the palace. Other subjects: young people running errands for their elders, whites ignoring the inconvenience of doing business during the heat’s height. Were the Europeans whom King Mwenda had demanded fealty from also in important relationships with her? Or only those she knew personally, such as Sir Matty?

No one stirring about recognized her without her attendants, and Mwadi reached the palace steps quickly and easily. Sifa still slumbered in the courtyard; Lembe woke, but fell in immediately with the princess’s pretense of being on her way to the bottom of the staircase that climbed from courtyard to rooftop.

For Lembe to do otherwise would have been to alert Queen Josina to her inadequacy. It would have been to admit that she’d neglected to do her job. Instead, when the queen came out onto the roof through the door of the interior stairway, her serving woman was diligently oiling the carved wooden stand of one of her holy hives.

Mwadi watched the queen walk slowly between the tubs containing her budding flowers and fragrant blooms. Reaching the sheltered platform where the princess reclined, Queen Josina paused to observe her woman at work.

“How is my brother?” Mwadi asked dutifully. She sat up and reached beneath her couch to retrieve the cloth-swaddled shongo and began to unwrap it.

Her mother stepped onto the platform and sank to the cushions beside her. “Well enough. The disease is coming to accept his superiority.” She swung her head one way, then the other, checking for any who overheard them. None of the other wives were visible; though supposedly it belonged to all, this garden was known as Queen Josina’s private retreat.

“All signs indicate Mwenda will take my advice on the succession. So eventually, Ilunga will rule over all the rest of our land just as he’ll rule very soon over the organism causing this illness.”

No he would not.

“Naturally, a position of such distinction brings with it a high measure of risk. We must guard him carefully…”

Josina’s long, proud eyes rested lightly on the bundle occupying Mwadi’s lap. “What are you about to show me?” Not waiting for Mwadi’s answer, the queen twitched aside the last of the veiling headwrap. “Ah. Is this—this is the knife your father threw!”

“Yes. I pulled it from the atolo tree. That means I—not Ilunga— am my father’s heir.”

Her mother smiled with closed lips. “You are his heir when he says so.”

“He will! He has to! Mother, you can help me to persuade him of my rights!” Mwadi took the shongo by its handle and tried to lift it from her lap.

Josina’s hands barred hers from rising. “Are you sure you should do this?”

She drew back, staring. “Of course I am!”

“Are you sure this is how to get what you want?”

All certainty drained from Mwadi’s head. Why would her mother object to her becoming queen? Why would she favor buffalo-headed Ilunga?

“Do you even know what that is? What it is that you want?”

“Everything! I want everything!”

A wider smile now. “Yes. You are truly my child.” And now her mother’s long, strong fingers curled over Mwadi’s own, reinforcing her grip on the shongo. “We will have it. Everything you want. Trust me.”

Mwadi had always trusted her mother. The question had always been whether her mother trusted her in return. Some secrets, the queen kept saying, it was impossible to share.

“Can you tell me how we will win?”

“You know that I am an initiate in the mysteries of the Yoruba, a priest of the orisha Oshun, yes? She who is the owner of wealth and learning?”

“I do.”

“She who invented the form of divination I practice. She who holds high her golden light to show me which path of the many I can see that I should take. Which leads most surely to my desires.”

Queen Josina’s exploration of foreign cultures was well-known— but had adoption of foreigners’ beliefs undermined her faith in her daughter’s abilities? Or did it somehow, by some devious means, support it?

“Your desires?”

“We are in harmony. I have learned the best melodies to play, the best places in which to move our feet.” The queen stroked the back of Mwadi’s clenched hand. “You must relax. As I said, trust me.” She beckoned, and Lembe abandoned her task to approach the platform.

“Accompany Princess Mwadi to Prince Ilunga’s chambers,” the queen instructed her serving woman. She leaned forward, speaking softly into her daughter’s ear, again stroking her hand. “You’ll give this to him for safekeeping.”

“To Ilunga? No! Never!” She lowered her voice, too, but fierceness filled it, hardened it the way blows and heat harden iron. “I! I will be this country’s rightful ruler!” She jerked her hand, trying to free herself—and the shongo—from Josina’s grip. She couldn’t.

“What if I agree with you on that point?” The queen was whispering, was close, her cheek touching Mwadi’s. The sweet scent of her hair oil threatened to wipe out all other smells, all sights and sounds and—

Mwadi stood. She swayed only a little, only a moment. She kept her hold on the shongo. So did her mother, which Mwadi found steadying. “Then you do? You agree and acknowledge—”

“Listen to me! Can’t you tell? Stop your insolence and obey me!” The queen stood too. “I know what I’m doing! I know this reality! I am ready to enter it—though if Oshun had not prepared me for your stubbornness I would have you poisoned!”

Quickly Josina wrested the shongo away from Mwadi’s surprised grasp. But only to hold it before her, between them. “You will present this to your brother. You will explain to him that you found it at the atolo’s foot, in a bowl filled with black sand such as we use for metal casting. You’ll make sure others hear your story, and that they repeat it.

“Do these things and anything else I instruct you to do. The throne and the land will be yours.”

June 1916 to June 1920

Kisangani, Everfair, to Cairo, Egypt

Should he lie? Prince Ilunga shifted his weight from one aching elbow to the other and gazed away from his sister’s gift. Then back. Resplendent on a fur-covered cushion it lay, his father’s first ceremonial shongo, a three-lobed promise of sovereignty. He who pulled it from the trunk of the atolo tree was to be named King Mwenda’s successor.

Should Ilunga claim the feat of retrieving it as his own? With the shongo in his possession, his claim would have real weight. It would ease the pricking soreness lingering from that earlier attempt, that ugly failure seen by all.

But what of those who’d seen Mwadi bring the shongo to him here? The guards outside his door? Or the flat-chested woman seated by his bed, the one his mother had assigned to attend to Ilunga as his illness receded? Not to mention anyone his sister might have met on her way to his rooms. Not to mention his sister herself, gone now. Gone to report to someone? To his mother?

There was no hope of untangling the threads of Queen Josina’s intricate plots. He must just believe she always put his interests first, as she swore she did.

“Why does my sister want it, anyway?” he grumbled.

The flat-chested woman spoke, startled. “She doesn’t! She gave it to you!”

He ignored her words. But her presence was not unwelcome; though you couldn’t call her attractive, at least she was a woman. He was young and needed practice. “Here. Use some of that salve on me. My limbs—” Clacking beads interrupted him as his mother swept through his bedchamber’s door.

“Queen!” The woman—he ought to learn her name—dropped to the floor. “Your son’s health improves by the hour. I was going to you with my news as soon as those bringing the evening meal arrived.”

“No need for that.” Josina touched the woman’s shoulder and she got up. “I see his progress.” An arched brow and the delicate flare of the queen’s nostrils indicated her approval. “He’ll be able to join his father tomorrow when he holds court.”

“Is that when we’ll receive the Portuguese envoys? Are they on—” A sharp glance from his mother stopped the prince’s questions mid-spate.

“The secret envoys spent last night in Mbuji-Mayi, and they rest there again today to observe a feast of their religion.” She paused and he had time to absorb the full strength of her emphasis on “secret.” “Rosine, go fetch the prince’s evening meal yourself.”

The poorly endowed woman left. No great loss. The coaching in diplomacy Queen Josina gave him once she was gone more than compensated for missing a chance to flex his love muscles. During the formal reception held for the Portuguese the next day, and in all his dealings with subjects and foreigners afterward, he did his best to remember her teachings.

Regularly she received visits from foreigners—often from those who had initiated her in her religious mysteries. When these visitors departed she would spend long night hours treading intricate dance patterns to music audible only to her ears. Some whispered that his mother was mad. If so, it was a cunning madness.

“Do not reveal the extent of your intelligence to those who assume you lack it,” she counseled him, again and again. “Play the fool in public and in private act the sage, and you’ll both surprise your enemies and please your friends.”

He watched as she accepted without protest the Portuguese ambassadors’ reluctant refusal to speak to the other European governments on Everfair’s behalf. Later, in the markets following his country’s surrender to the English, Ilunga learned how invisible activity—spying, magic spells, nested schemes—bore visible fruit. Despite the attacks on their sovereignty instigated by Thornhill and other British agents, his mother cultivated Everfair’s ties to certain of England’s factions. Because, she said, “Our enemies are made of more than one kind of cloth.”

As the seasons passed, Queen Josina encouraged Ilunga to dig his own information channels and direct their flow. She expected him to use these to help her keep up with schisms developing between those who planned a return to Europe’s fast-vanishing superiority.

The so-called War to End War resulted in a litter of smaller conflicts, most fought with words and smiles, in hidden rooms, on metaphoric battlefields. Judged a harmless playboy, Prince Ilunga was easily able to observe the Europeans and their surrogates as they jockeyed for knowledge and position. He journeyed from city to city, avowedly in pursuit of pleasure: west to Lagos, south to Maputo, east to Mogadishu, north to Cairo.

Where, at the age of thirty-five seasons—eighteen-and-one-half years—he found his first real friend.

Deveril Scranforth grinned when Ilunga introduced himself as the future ruler of Everfair, and leaned back to balance his wooden chair on two spindly legs. “Ha! One day you’ll outrank me, then. But for now—” Without looking he stretched wide both arms and hooked each around the waist of a deep-chested beauty. “—for now, I’ll be teaching you a thing or two, what? And you’ll be grateful for that—and show it!”

Smoke from their host’s hookah drifted between them on its way to the night-curtained windows. Attending this soiree was part of the standard plan Ilunga’s mother had devised for gathering intelligence: woo the offspring of embassy personnel and allow himself to be drawn into their social groups.

Attendance was part of the standard plan, making this a completely unremarkable evening, but ever afterward Ilunga remembered it as the beginning of a new phase in his dedication to savoring the world’s glories. Heightened awareness of his surroundings, helped on by the judicious consumption of cocktails, filled him with the sense of his surroundings’ divinity: the satin sheen of the throw pillows scattered about him on his divan, the jewels winking in a passing guest’s cuff links, the sweet residue of honeyed melon coating his lips, the tinkling chime of the golden chains adorning the wrists and ankles of the laughing woman who leapt up from Scranforth’s lap and snuggled cozily onto his own— despite his weak protests.

“Not a virgin, are you?”

As if Ilunga were still a boy! “No!”

“Good. Nothin wrong with it if you were, but I’d want to start you out a bit slower.” The white crooked his finger and two more beauties congealed out of the crowd to stand beside him. “Which of em d’you want? All three of em? Like to keep one for m’self.”

To go from the glittering heat of the party to the dark fragrance of the house’s fountain-fed garden took only a few steps. Only a moment. And then the prince was enveloped in flesh. Above, below, on either side, perfumed skin slid and slipped against his clothing. Then against his nakedness.

Touch receded, returned, receded, returned, new waves rippling over old ones like the music of the fountain waters rising and falling somewhere nearby… like the fickle breezes laden with the party’s distant murmurings, or the thickening breaths of the women wrapping him in pleasure.

Then Scranforth’s voice came crashing through their panting sighs: “What d’ye say? Good play? Best hoors in Maadi—in all Cairo! Agreed?”

The soft lips kissing Ilunga’s eyelids went away. He opened his eyes and his mouth, about to bellow furiously at the European’s interruption—but the soft lips came back, to graze his jaw and cling moistly to the ridges and valleys of his throat—and his delight at this found its reflection in the pale, half-shaven face hanging over him.

The prince realized he wasn’t actually angry.

Delight mirrored was delight doubled. Bliss upon bliss proved this new truth. To receive a caress and cry out at its shivery progress—from spine to buttocks to tight and tingling testicles— was to share and deepen its effects.

Was this increase in his arousal a sign that Ilunga wanted sexual congress with the white man? He tried asking his mother. Sometimes he believed she knew him better than he knew himself. But the coded messages he sent her went unanswered. All the queen responded with were instructions: stay in Cairo, enroll in Victoria College, rent a home there that his sister Mwadi could run for him.

His father wouldn’t blame him for a trait only Europeans and missionaries abhorred. Would he? Probably not. Although Ilunga’s usefulness as King Mwenda’s heir would perhaps be compromised… No. That sort of thinking belonged in the head of Queen Josina. Who, if she said nothing of her son’s predilection, must not consider it to be a problem.

And for him it wasn’t. Adventures with Devil—so Ilunga came to call his new friend, adopting the pet name employed by his fellow students—filled most of the prince’s nights, and quite a few of his days as well. The white man knew the town’s best brothels. Even more conveniently, he introduced “Loongee” to several women willing to entertain them for no money—though not exactly for free, as Ilunga quickly learned.

His first such encounter was with a buxom, cheerful matron whose nephew controlled the stock certificates of the Great Sun River Collector Company. She was easily satisfied. In addition to plowing the slick delta between her thighs—Devil stationed titillatingly nearby, ostensibly to watch out for the woman’s husband—he only had to purchase fifty shares of the company, at a surprisingly moderate price.

But soon the prince learned how to fend off these requests. This meant that sometimes, to his regret, he also had to fend off the proposals of erotic exercise they accompanied. Enough of those remained to keep him happily occupied, though. And despite a couple of petty disagreements, and one serious quarrel involving a firearm, he made sure to include Devil in any activities of that sort.

Ilunga dedicated an entire suite of his Maadi villa to sexual pursuits. He arranged a door communicating with the room where Devil often stayed. Once or twice he invited others to visit, hoping to experience the same intensified gratification in their presence.

As far as Prince Ilunga could tell, his experiments failed. He felt no comparable increase in sensation when he shouted his satisfaction in the hearing of his sister’s European protégés, the Schreibers; no wider or even equivalent overflowing of deliciousness when he hosted other college friends for similar nights of sexual indulgence.

Nonetheless, his efforts made a difference.

How? Chiefly through his memory. Ilunga knew he was reaching for connection to others. He was aware that he cherished the touch of the women who attracted him, and that he yearned to share it. He realized how he longed to drench the strangers of the world in these women’s musk, to be soused in their sweat, to drown in it while drowning his white companions with him.

Memories of these desires dug their grooves deep into his mind. Incompletion kept them fresh and sharply edged.

Memories, like all stories, want to tell themselves. Asleep, Prince Ilunga dreamed that his fantasies came true. Awake, he forgot the specifics of how that occurred. But the happiness his dreams left behind haunted him.

Awake, the prince pretended stupidity, as Queen Josina had advised him to do. He acted as though ignorant of Devil’s plan to use him to access Everfair’s mineral wealth—and of some points in that plan he really was ignorant, because ignorance was easier than action. Ilunga always preferred to avoid unnecessary effort.

In fact, it was Devil’s drives rather than the prince’s own unsteady ambitions that moved most things forward—especially things concerning the succession. Much of what the European wanted to do depended on Ilunga inheriting the throne. So in between their college’s lectures on the histories of dead empires and their evening assignations with willing women, Devil did his royal friend’s tedious yet necessary political work.

Who, then, do you suppose gathered and treasured together Prince Ilunga’s unrequited attempts at blurring the boundaries dividing him from the rest of creation?

Who do you think?

CHAPTER ONE

December 1920

Tourane, Vietnam, Aboard Xu Mu

Dragons. Best to follow them. Bee-Lung looked up at her brother. His long, appropriately handsome face became clear as the winch cranked her higher, toward the aircanoe’s open hold. His expression was calm. Those born in Dragon years expected to lead others even more than they enjoyed doing so. He really was the perfect node. The decision to share her specially bred new strain of May Fourth’s Spirit Medicine with him was proving wise.

Nodding acknowledgment to the Bharatese man on the crank, Bee-Lung hitched her robe tight against her hips and thighs and hopped over the cargo basket’s low rim. Normally she wore trousers, but her appearance at the French administrative palace had merited the wearing of this concoction of peach-colored silk trimmed in crimson cord. It seemed to have done the trick; she would have to store it properly till the next stop on their trip.

But first to tell Tink. He was already walking toward the hold’s narrow door out, sure she’d be behind him. She smiled at his back and ran forward. He paused at the threshold and turned, one foot still raised to step through. “Success?” he asked. The beginning of a furrow indented his brow.

“Of a sort.” Without moving her head, Bee-Lung indicated the Bharatese man with her eyes. He had joined them too recently to be trusted, his inoculation only taking place today.

“Come.” Out the door, along the corridor, to their shared cabin in

Xu Mu’s gilded prow. “Now.” He closed the thick cotton curtains and pushed a sack of dried mushrooms out of his path to the glassed window. Porthole.

“They’ve stopped short of giving consent for the cable’s inoculation, but they won’t stand in our way. As long as no one can implicate them.”

“The French wish to seem ignorant of what we’re doing in their colony?” Tink’s voice had the sheen of sarcasm.

“So I interpret our interaction.” A crate of clay Spirit Medicine containers on the floor—deck—rattled as the aircanoe rocked in a momentary gust. “Naturally we must prepare to leave as soon as the spores are distributed. But my recruits will tend the threads they produce to expansion and fruiting, and will make sure the resulting conduits connect with the ones we started for our May Fourth friends.” Ducking under a small hammock filled with empty paper envelopes—she would use them to organize future botanical samples—Bee-Lung made her way to the cabin’s second and larger porthole. It was shaded. She pushed the white pleats to the round frame’s bottom and looked out over the city the French called Tourane. Xu Mu faced away from the mouth of the Han River and away from the telegraph cable’s landing station on the shores of the East Sea. The red roofs under which Bee-Lung had lately intrigued lay almost directly below. The French invaders’ mooring facilities were barely adequate—a rope was all that held the aircanoe to their mast.

Low clouds gathered and parted and gathered again, veiling the inland mountains in pale obscurity. “At least it’s warm,” her brother remarked. “If the rain keeps off we’ll have no trouble tonight.”

“No need for you to go yourself, then.”

“But I want to.” Of course he did.

“No need,” Bee-Lung repeated. Uselessly. Not just Dragon, Metal Dragon.

“Would you rather I sent you?” This was a jest on Tink’s part; it had been determined earlier the differing roles she and her brother would assume on this voyage.

“No.” She pulled the shade back up and frowned. “They’ve already seen me.”

“Ha! They’ll never see me! I’m not getting caught!” He went to crouch over the jars of Spirit Medicine. “They accepted the tea we brought them without noticing?”

“Even so.” The threads of Spirit Medicine that they had secreted in bundles of fragrant tea leaves were so thin as to escape detection. Stored in the palace pantries, these would be available to May Fourth’s new kitchen agents for later inoculations. Of which there would assuredly be many. “Enthusiasm for our venture will greet—”

A scratching at the bulkhead interrupted her. The Bharatese man shoved the door’s curtains aside and came in holding a tray. “Raghu!” Yes, that was his name. Of course Tink knew it. “Are you ready?”

“And eager!” Light from the glowing sponges in his tray of bowls winked off of Raghu’s sudden grin. Like that, it was evening; the day had been dark enough that the change had slipped past her without fanfare.

Bee-Lung took a sponge lamp and hung it from its hook on the cabin’s ceiling. One of her favorite discoveries; the radiance of the powder impregnating it was fired by water. So gentle its shine. So sad, like a setting moon.

There was no reason for sadness. Tink would be fine. Her trepidation over the deployment of a gang numbering unlucky four was mere superstition. The May Fourth Movement’s very name repudiated such backward notions.

She took a second lamp to hang.

“You should sleep,” Tink told her.

She tugged fretfully at the tight cuffs of the silk robe’s sleeves, which had crept up to pinch the fat of her upper arms. “I should get out of this abominably restricting dress.”

“And then sleep.”

While changing to her accustomed clothes, she imparted the intelligence obtained by the kitchen agent regarding approaches to the cable’s terminal station. Then, because it was her policy to obey her brother, even when he didn’t realize he’d given an order, Bee-Lung did manage to sleep—for several hours. She woke well before sunrise to dimness and silence. The water fueling the sponges would have partially evaporated by now, so the cabin’s dimness was to be anticipated. But not its silence. The lamps’ low glimmering showed that the hammock beside her own hung limp. Empty.

Tourane, Vietnam, Aboard Xu Mu to the Governor’s Palace

Seated with three of his chosen kin in the cargo basket, headed down to his first ground sortie in service of May Fourth, Tink felt a happiness he hadn’t known in years. If there was no conventional beauty left in the world for him since Lily’s death, he could at least be of some practical usefulness. The Chen twins seemed filled with the same high hopes for the mission he himself held, giggling as they hunched protectively over the braided coils of spore-laden root sheaths. Before the basket’s descent plunged them into the starless night’s darkness, Tink could see that Raghu’s expression looked less sanguine. Then there was only his scent to go by: the Bharatese man’s sweat, bitter with nervousness; his noxious inner winds released to be dispelled by gradually rising offshore breezes, which carried the sweeter smell of dying kelp. At last came the muddy odor of the freshly trodden road to their target, as promised by Bee-Lung’s intelligence.

Climbing from the staging platform down to the ground along the bamboo stairway at the palace’s back, they encountered only one guard. Before he could raise others, Chen Min-Jun grabbed him by the throat. His scream softened to a grunt. “Come with us,” the girl suggested, her strong hands twisting left and right, then loosening.

“Or decide to stay,” said her sister. “In which case we’ll be forced to kill you.”

No surprise that the guard became at least a temporary recruit.

Between the homes of colonialist collaborators clustering near the palace’s walls they walked—quickly, quietly, avoiding the treacherous, gravel-strewn entranceways of the more elegant establishments. Then these were left behind.

Removing their lone lightsponge from his shirt, Tink lowered it to soak in a puddle and activate. He squeezed out the excess water and returned it to its former home, his body and clothes serving as its shade. They should not rely on their eyes alone. It would be best to frame their perceptions in the fashions nourished by the Spirit Medicine while on this mission.

Soon the tingling air of the woods encroached more closely, and soon after that it enveloped them. Tink wanted to rest here, to lie among the enchantingly damp fallen leaves as if he, too, had come to the exact right place. But the road. The mission. The spores.

The target. At last they’d reached it. Fragrant, new-turned earth, steaming with life, sat wetly mounded over the trench in which the cable traveled from its landing station in the bay to the terminal house on the forest’s far side. Here they would insert the latest of their spore batches, whose emerging threads would reach along that cable’s length to find the previous, the next, the next…

He waited for Raghu, who lagged behind the twins and their captive. “Tools?” From a sling over his left shoulder the man removed a pair of collapsed shovels. Unfolding the one handed to him, Tink sank it into the soil. He directed the Bharatese to start digging a few paces farther from the road.

The actions he performed were pleasurable: sinking in the shovel’s blade, lifting out the muck of knowledge, heaping it up next to one serenely expectant hole after another. He couldn’t delve too deeply; the holes’ round sides wanted to melt and sag. But once in place and active, the spores would sense their goal and reach down for it with quick-growing tendrils.

When he and the Bharatese had excavated a dozen of these miniature gullets, they switched duties with the twins, tending the prisoner and watching for intruders while Min-Jun and Jie-Jun unspooled the precious root sheaths into the waiting orifices. This far from shore there would be no steel wire wrappings—only rubber and gutta percha layers to protect the buried cable’s copper core, materials that would help as much as hinder the growth of the spores’ tendrils. The Chens poured mud back into the holes. It overflowed them.

Was this spot too wet for the fungus to flourish?

Tink felt how long it would be till dawn. “Onward,” he decided.

The covered trench went straighter than the road, but in the same general direction.

As they came nearer to the telegraph’s terminal station, the waters soaking the black earth drained somewhat away. Though still flat to his useless eyes, the land slowly rose, so that in good time an orchard of mangos surrounded them on both sides. Excellent. This was a sort of terrain Tink was very familiar with.

The digging this time was not much more work, though they made the pits deeper. Another twelve. That ought to be enough. Again he and Raghu traded with the sisters. But the prisoner had been flirting with the girls, and he sulked, unhappy at the change.

“What’s your name?” Tink asked. If he could, he would learn from the guard himself how best to persuade him to their side permanently.

“Zhou Yong-Lei.” Honest pile of rocks. Well, one could gain purchase there, if one were stubborn.

“And of what do you dream, Master Zhou?”

“I—”

“Terrorists! Seize them!” Shouted orders and blinding white beams shattered the orchard’s dark calm. Off of the road poured a clotted flood of frightened-smelling men. BANG! BANG-BANG-BANG! Rifle fire from two different points flew mere handsbreadths from Tink’s face. He fell to embrace the earth, catching at Zhou’s clothes to drag him down too and save him. Another explosion and the sudden salt of spilling blood told Tink that he had failed.

Sadness. The guard died, life leaking soundlessly out of his wounds and into the orchard’s accepting roots. Tink surrendered to the men—they were all men—who had shot him. No chance now to win Zhou over to the right side. Hustled toward the road and back the way they’d come, Tink wasted precious time in regret. Only as they left the countryside behind did he begin to return to full function.

Coals smoldering in iron baskets flanked the wide stairway leading to the palace’s grand entrance. By their smoky light he saw that the Chen twins still accompanied him, though Min-Jun had a dark swelling on her right cheek. Twisting as far as his captor’s grip allowed, he made out Raghu’s slumping form at the group’s rear, supported between two soldiers.

They didn’t climb the stairs. A pair of soldiers at the bottom challenged them in French. Tink had learned a little French from Lisette and the Poet. Only a little, and long ago, and this version was differently accented. His sister had made a study of the language for diplomatic purposes. Not he. The tones of the challenger’s and the respondent’s voices told him more than the shapes of their words. The challenging man seemed satisfied with the other’s answer, but rather than lead them up to the governor’s receiving rooms he took them to a shadowed servants’ entrance near the building’s southwest corner. With a last deep breath of the night air in which Xu Mu flew, so near, so unreachable, he followed his captor’s insistence within.

It wasn’t all bad. The lights were far apart, but steady and shielded with glass. His vision was restored to utility. They walked to the end of a corridor and turned left. A door on their right would have delivered them to the bamboo scaffolding and stairs up to the roof platform and the aircanoe’s mooring post. But that door was shut, and they turned away from it, into the palace’s heart.

Or if not into its heart, if hearts must lodge higher in metaphorical bodies, then into its rectum. A small chamber, poured concrete for walls, no windows, square flagstones paving the sloping floor save for a wide, shallow hole at its center. Old odors of stale sweat and cold embers and roast—pork? monkey?—fought with the odors they carried with them: the knowing mud and the new blood and the trace scents of gunpowder, steel, the fat greasing the soldiers’ boots and the laundry soap lingering in their uniforms.

The soldier who had hauled Tink into the room flung him across it. He fell on his side. The flagstones soothed him, cool against his exposed skin where his short trousers were torn. The Chens landed beside him, then Raghu beside Jie-Jun, grunting and trying to stand again at once.

“Attawndayzeesee.” Wait here. No doubt a joke; the soldiers were all laughing as they left, laughing even louder as they locked the door’s rattling lock.

No electricity. No light. Tink turned the sponge around inside his shirt so that it shed the brightness fed by his perspiration out onto their surroundings.

“They didn’t chain us!” observed Jie-Jun.

“Why should they need to?” Raghu asked glumly. “We’ll never escape.”

True, perhaps. By the smell of things the door out was guarded. The room’s walls stood as stout as such walls could stand; given time they would crumble, but for now—the floor? Tink half-rolled, half-crawled to the bared earth at the room’s focus. It actually stank—even before he had taken the Spirit Medicine, Tink would have noticed its reek of charred wood. His heightened sensitivity to chemicals revealed nastier details: a spatter of urine, and small but insistent clots of vomit. And the sweat was reminiscent of grief and fear. These things combined with the faint hints of old roasted meat to tell him why they’d been brought here, what they’d been left here for. Torture.

He buried his fingers in the sullied soil. As always, it lived. But sourly, blindly, in solitude. To make contact with even a rudimentary core such as they had started growing on the palace grounds would take too long—weeks, during which time he’d be unmoving and apparently unconscious. And preferably unobserved. Unlikely.

The ceiling? Tink got to his feet and pulled the sponge from his shirt. He raised it high so its soft brightness showed him that yes, as he’d sensed, there was wood above his head. But wood long dead, infused with some decay-retardant poison, so that there was no communing with it, no way to use it to tell his sister of his whereabouts.

The Chens came to kneel beside him, eyeing him expectantly. They knew him for a node. “We must simply wait for Bee-Lung to find us,” he informed them. Eventually she would catch his scent. “She’s bound to come soon.”

Tourane, Vietnam, Aboard Xu Mu to the Palais du Gouverneur

Of course both of the cargo baskets were in use right when Bee-Lung needed them. Xu Mu’s loaders had filled them the prior evening, doing the heaviest of their labor before the warmth of the day. She hurried to put on the stupid peach silk robe again, but by the time she arrived in the hold the industrious workers had already lowered one basket to the platform; the other dangled in midair. Obviously it had gone too far down to be recalled.

Breathing as calmly as she could manage, Bee-Lung composed herself to stand out of the way, a distance from the open hatch. The winch operators unwound the cable with what seemed to her unnecessary deliberateness. Surely the second basket’s journey wouldn’t take too long—the landing platform was no farther away from the gondola’s hold than the bottom of the aircanoe’s envelope was from its top. Yes, the gifts of porcelain it contained were delicate, but very carefully wrapped. She had delayed sending them down till now to make certain of that. This was her fault.

The full basket reached the roof’s level without incident, was hooked and hauled into place, and at long last the winch line was attached to the emptied basket. Up it came and in she got.

“You won’t go alone?”

That had in fact been Bee-Lung’s intention. But the question came from Kwangmi—the only woman Tink had voluntarily sought out since his love’s death, and the core member who—though she was deemed unnecessary to the sowing mission—would have made them five rather than unlucky four. Bee-Lung ought to overcome her disdain. “Not if you’ll join me.” She climbed into the basket first, then held out her hand to help the Korean, who despite her name was dark-complexioned. “Shining Beauty” indeed. Trust her brother to find the unorthodox attractive.

“Hurry! Quickly!” Ignoring the lurch and sway of the cargo basket’s initial drop, Bee-Lung pleaded up through the hatch for the workers to lower them fast, faster! Not till they reached the platform did she realize she still held Kwangmi’s hand.

Bee-Lung loosened her clenched fingers. A rag-clad loader offered his dirt-smeared arm. She pretended she needed it, clung to it, and with a false show of age tottered stubbornly away from the bamboo stairway running down the palace’s back, dragging the loader and his arm alongside. Kwangmi, smart if not conventionally good-looking, followed her example. Yesterday’s intelligence— how long it seemed since she’d received the skinny little kitchen maid’s report—said there was a door to the attics on the inner slope of the east wing’s roof.

Yes. A short hop onto the regrettably slick tiles—an inadvertent slide halted by Kwangmi’s swift snatch at the peach dress’s collar—a gap in the door’s shutters—she was in.

A round window covered in brown paper provided some light, but it was in the western wall and not exactly bright. Bee-Lung let the air currents tell her where she was, what surrounded her. Mostly empty space. A pile of trunks filled the corner to her immediate left. A velvety cluster of bats hung from the peaked roof’s rafters, the white of their feces a stark circle on the attic’s dark floor. Which way down? The bats would not know.

Kwangmi entered behind her. “Bar the shutters,” said Bee-Lung.

The sounds of Kwangmi’s searching ended in satisfied mutterings and the knocking of wood on hollow wood. “It’s done,” she pronounced, padding forward on rubber soles. “No one will follow us in. Can you smell where he is?”

“Vaguely.” Bee-Lung shook her head. “He’s below us. Quite a distance—” Maybe she should have presented herself formally instead of entering this way. Who knew how many floors lay between her and Tink? Was it too late? Perhaps not. After all, only the no-doubt lowly loaders had seen them arrive. Perhaps Kwangmi could be directed to render occult aid if Bee-Lung could find her way to a regular receiving room. There she’d do her best to distract the colonial officials with a petition for their help in solving the mystery of Tink’s disappearance—a mystery Bee-Lung suspected the French themselves of causing.

Wherever the exit to the rest of the palace was, it would not reveal itself to her if she simply stood in one spot. “Come, Kwangmi,” she commanded, walking past. Together they moved through the door in the wall dividing them from the attics’ main area.

The new room was wider, and higher ceilinged. And emptier. And still so much dust! She saw no nearby windows, but there ought to be vents—

“CHUHH!”

No! Bee-Lung whirled, but before she could silence her, Kwangmi let out two more loud sneezes: “CHUH! SHH-CHUH!” Then she had her hand over the woman’s disgustingly wet nose and mouth.

The sneezing fit stopped. They stood in a ringing quiet. Faint murmurs from the bats in the previous room ruffled its surface. Bee-Lung plunged deep underneath the noiselessness, sinking into the slumbering lumber of the building, swimming with the pollens floating—floating down? Down! The wood confirmed it, and also what she now remembered of the sneezes’ echoes.

Removing her hand momentarily from Kwangmi’s face to wipe it on the silk robe, which was good at least for this much, Bee-Lung brought it back up to pinch the woman’s nostrils shut, then drew nose and head low enough that her lips touched Kwangmi’s naked ears.

“Follow me to the storey below. But stay hidden. From there go where you detect his scent.”

Softly as she could, Bee-Lung crept ahead and to the left. These stairs must connect with the set running from kitchen to servants’ quarters. She began her descent, then paused. Now she recalled seeing a narrow door in the cramped back passage’s plastering, too high to reach without a stepladder. Would she hurt herself? Kwangmi would be fine. And so would Bee-Lung; she’d have to be. Pulling free a few pins, she disarranged her hair. She rubbed her eyes red and lamented that the steps on which she stood seemed to have been swept clean. But doubtless the robe’s hem had gotten dirty enough during her trek across the dusty main room. She checked to make sure there was no visible sign of the Korean woman. No. If Bee-Lung hadn’t sensed her, she would never have known Kwangmi was there.

Smiling, Bee-Lung began to scream. Like a unicorn she thundered down the rest of the stairs to pound on the locked door at their bottom. “Demons! Demons!” she screeched. “Save me! Save me! Demons!” For greater effect she added a string of wordless yelps.

Soon the door opened and two wiry men with muscle-knotted arms pulled her out. Servants—not her target audience. She clasped them to her and wept, acting too frightened to answer their questions. They supported her ostensibly uncontrolled steps and steered her helpfully toward the front of the palace, where the Frenchmen worked and lived. But she balked at the broad stairs leading down to the ballroom and library levels—her task was to divert attention away from those lower floors and give Kwangmi a chance to free Tink.

Her ears caught the click of a metal latch retracting. It was followed by a phrase: “Portayzellah.” A woman’s rich scent flooded Bee-Lung’s nose; she looked up to see a proud, high-browed face peering from a doorway to the stairs’ right. She had not met this one yesterday; judging from intelligence she’d gathered this should be the gouverneur’s wife’s primary attendant, Madame du Strigile.

The room into which the servants ushered Bee-Lung was not as spacious as those in which she’d been welcomed the day before. A narrow bed on one side, chairs with embroidered cushions on the other, arranged next to a small and totally unnecessary fireplace. Bee-Lung fell onto the bed as if in a faint. It stood beside a pair of open windows and so was blessed by a cooling breeze.

“Keteelareeve?” said the Frenchwoman. Bee-Lung’s recall of the language was returning. Qu’est-il arrive. What was wrong. Moaning, she modified her babble, murmuring now in French her distress-fractured claims of fiendish assault: “Came upon me where— snakelike wings—horrible laughing teeth—”

A cup touched her lower lip and she gulped water from it gratefully. “Fetch Doctor Blanchet,” the madame ordered. A servant left, but four others took his place. The room and the corridor beyond were nicely crowded now. “Clear the—”

Desperately Bee-Lung sat and grabbed for the madame’s shooing hands. Won them. “NO! Don’t leave me! Don’t let anyone go anywhere alone!” Bad enough that the important ones, the soldiers, were still missing.

The madame’s high forehead ridged in annoyance. “Really!” Fortunately at that moment the smell of a European man asserted itself. The gouverneur! His bushy brown beard covered his face like a prickly shoe-cleaning mat. Gold spectacles shivered on his unremarkable nose, reflecting away her sight. “What’s all this nonsense? Haven’t I enough to deal with already, holding prisoners for that Christ-beloved cable company? House servants are your responsibility!”

He was leaving! Bee-Lung jumped to her feet and pushed through the throng. “Master! The demons want you! You!” The gouverneur paused in his ponderous pivoting.

“This is no servant of ours!” the madame sneered. “Don’t you know who works for you?”

“If it’s not ours, what’s the little monkey doing in here? A beggar? Turn it out!”

“She’s the ambassador, fool!”

Close enough now, Bee-Lung seized the gouverneur’s wrist and clung fiercely despite his frowning attempts to wrest free. “They wish to eat you up!” she insisted. “You must—”

“Here! Let me go!”

On the contrary, Bee-Lung buried her face in the man’s satin-covered chest, wrapping his fat waist in her other arm. Temporarily, the hands of servants pulled her away from him. But sagging back as if in a faint, Bee-Lung fell against her captors. They staggered and dropped her. She crawled back to the gouverneur and grabbed at his ankles. He kicked. She howled and pleaded. The madame strove vainly to insert reason into the scene. “Let Blanchet come treat her— If only you will stand firm, Antoine, she cannot possibly move you!”

The gouverneur ignored this sage advice and kept kicking. The sharp toes of his stinking leather shoes hurt. Bee-Lung slipped them off his feet one after the other, which perplexed him. “To me! Guards! Guards!” he yelled. At last, at last, soldiers began arriving. Dark blue uniforms swarmed up the stairs and filled the passageway. By this time she’d been dragged to the room’s threshold and had, between kicks, an excellent view of proceedings. And an even better perspective via her other senses.

Not all the palace’s soldiers had run to the gouverneur’s defense. A few, faintly distinguishable, remained in the service area four stories below her.

However, Tink did not. His scent now found her mainly by way of the madame’s open window, with Kwangmi’s and that of some familiar others joining it. They had gotten out. Success!

With a show of reluctance Bee-Lung finally allowed herself to be detached from the white man’s ankles.

Tourane, Vietnam

Thorny hedges laced with drooping, brown-spotted leaves sheltered the path between the kitchen and formal gardens. Fat berries colored a fiery orange hung at intervals. Tink saw Kwangmi snatch a few, then ran to follow her into the shadow of the south court’s tall fountain.

“We’re hidden here?” Raghu asked.

Tink and the Chens were too busy slaking their thirsts to answer such a stupid question. “Not hidden,” Kwangmi told him. “Only unseen. For the moment.” She drank from the fountain too, then put a few of the berries in her mouth and began chewing them.

“For how long?” The Bharatese man rose nervously.

“Sit.” Tink tugged at Raghu’s sheer tunic. “Till we must board Xu Mu again.”

Raghu sat, but looked back at the palace, up at the aircanoe looming overhead, back, up, back, up—

Kwangmi spat the chewed berries into her palm. “Tear off the bottom of your shirt.” She spoke to Raghu.

“Me? My kameez?”

She nodded impatiently, then gestured to Min-Jun. “Come beside me. Please. Just the front, Brother.”

Tink placed a comradely arm atop Raghu’s shoulders. “Best to humor her.”

Grinning in embarrassment, the Bharatese tore his white cotton garment from side-slit to side-slit and gave the resulting rag to Kwangmi. She dipped it in the fountain and twisted it into a bandage, packing the berry mash into its pleats. With not a single glance at the trouser top Raghu had been so reluctant to reveal, she tied the makeshift poultice into place on Min-Jun’s black and swollen cheek. “Sister Bee-Lung says the healing properties of rose hips are fast acting. You’ll feel better soon.”

“Are we waiting for her?” asked Jie-Jun.

Tink peered around the fountain’s lowest aerial basin. “We were, but we should go.” Though no one was visible yet past the masking roses, the chase was on. Several palace doors had suddenly opened, and in the near distance he heard waves of sandaled feet crash out of them, their noise spilling loudly over the steady trickle of the fountain.

“We’ll weaken them—divide them! Let’s separate!” Even as he proposed doing this he dreaded a course that could leave Bee-Lung behind. He didn’t want to part with the twins, either, or poor Raghu, and certainly not Kwangmi, who had proved so useful so often. And yet how else—

“Yes,” Kwangmi agreed. “That was Sister’s plan. I will lead them to their closest temple of Christ, where the French, being superstitious, will avoid killing us. And you will climb directly to Xu Mu and rendezvous to pluck us off the temple’s high tower.”

“But surely—”

“It is in accord with our core’s wishes.” Tink knew she was right, felt it in his blood and glands. “No more arguing. No more time.” Urging Raghu and the Chens before her, she ran toward the street-side wall of the palace’s compound.

And he ran where he was meant to run, to the palace itself, to the ramp the stairs the landing deck the mooring mast, shoving aside five soldiers in his way. The Spirit Medicine lent him speed. One soldier, regrettably, went over the deck’s too-low rail. He bounced nastily as he fell; before he landed Tink had topped the mast and begun his swarming ascent up Xu Mu’s mooring line.

Some waft of information had reached high enough. The cargo basket was being lowered; Tink would easily be able to reach it with a few more pulls upward. He did.

Secure in the basket, Tink looked earthward again. The palace disgorged a hurrying stream of soldiers, his sister in her improbable peach dress in their lead. They cascaded down the steps to the carriage path and onward to the gate, in apparent pursuit of Kwangmi and the others. Faint shouts rose from a portly man in European costume walking briskly among the stragglers. Lastly, a woman also in European attire appeared. She stood in the middle of the steps and clasped her hands.

A light breeze scattered any scents emanating from the ground. Tink raised his eyes. The basket was nearly to the hatch. Already he could distinguish different cores by their individual members’ arms as they reached down to touch him, to learn what he could pass along of the mission’s success and the others’ safety.

“Cast off!” he cried as they hauled him into their embrace. “Immediately!” Two newer recruits scurried away to the prow to reel in the mooring line. Surrounded by the rest, Tink traversed the cramped corridor running aft between hold and bridge; as they went, some fell away to share his news with others in the crew. At the corridor’s end, on his own, he came to the companionway and ladder down to Xu Mu’s many-windowed steering and observation pod. It was narrower than the main body, feeling full when during flight four were stationed there. But even as he rushed to the lever bank on the pod’s far side he indulged himself in a burst of pride. The bridge pod had been his innovation, his favorite modification to the very basic aircanoe design May Fourth had initially adopted.

Xu Mu’s control levers jutted inward from the hull at waist height, just below the pod’s two rear-facing windows. Tink seated himself on the bench before them and pushed up the small switch lifting the barrier between the Bah-Sangah earths of the engine. Now they would mix and produce enough heat to create steam. In a quarter hour the steam’s pressure would suffice to turn the aircanoe’s propellers. But Xu Mu would need to fly to Kwangmi’s rescue sooner than that.

Outside the pod’s windows, the lowest clouds had torn apart to show those higher and thinner; now these began to melt like silver. No rain for a while, then, it appeared—but if the wind strengthened, trouble could develop.

A subtle shudder ran along the bridge’s woven ceiling. Well, if the wind caused problems they would have to solve them. Xu Mu was unmoored. His vista shifted as Tink maneuvered the aircanoe’s flaps and rudders, trying to swing its nose 180 degrees. Pitching, yawing, creaking, straining, Xu Mu struggled in and out of the wind’s fickle grasp till at last he saw the palace retreating slowly behind them. They rode the bay’s breath landward.

Normally he shared his bridge shifts with Kwangmi, he and one trainee keeping watch to the fore while she plied the control levers aft with another. But not now—he strode to the pod’s forward windows alone and there! There rose the Christian temple’s square towers, shedding the morning’s mist like smoke in the sunlight. The temple seemed somewhat to his south—Tink returned to the control bench to engage corrective fans—and was the aircanoe rising? Too high? He ran back and forth a few more times, and once, when Kang Woo-Hyun peered down the ladder to ask for instructions, he clambered halfway to the hatch to ask him how swiftly the crew might distribute themselves toward the bow.

“Will that not cause us to descend, Brother?” Woo-Hyun asked.

“Yes! But wait upon my signal!”

“What signal? How shall we—”

“Do I care?” he shouted. Clenching the ladder’s rails, Tink forced himself back under control.

“Those who have received the Spirit Medicine will sense my signal and relay it to any still waiting for inoculation.” That should work, provided he allowed sufficient time for transmission. He descended the ladder to check again on their progress. They had better not arrive too soon, or their passengers would not yet be in place.

“Leave the hatch propped open,” he shouted upward. “Bring Ma Chau to stand by it.”

A sudden calm struck. Xu Mu hung motionless in a thickening murk. A storm was brewing—out of what? Out of nothing! While preoccupied with coaxing the motiveless craft toward the temple to the west, Tink had discounted telltale signs of a squall coming in from the sea in the east. He knelt on the bench and scanned the sky anxiously. The pause in the wind might indicate that it was about to worsen—or that it would altogether cease for hours—which was likely if the associated precipitation was heavy enough—

A spatter of rain dashed against the glass. Another, louder, and then others, more, blending together, a constant flow, a bankless river and Xu Mu drenched and sinking, sinking, far too soon, with their goal now lost from sight.

How long had it been since he threw that first switch? The inexactness of the sense of time’s passage that the Spirit Medicine engendered in him was so annoying. Yes, all life was interdependent, and matching the aircanoe’s arrival at the temple with his kin’s was a most useful ability. Also valuable was the Spirit Medicine’s improvement in his piloting skills. But was the engine hot enough yet? The steam high enough? Could he call on its power now to drive them on through the blinding rain?

“Ma Chau!” he shouted.

“Mr. Tink?” So she called him, according to her people’s custom. “I do not smell the signal to send us lower.”

“No! No longer necessary!” If this were a junk they could row. If he were a giant he could set Xu Mu on his palm and blow. As things stood…

“Direct four good winch-workers to the hold. Make sure they’re ready to lower the cargo basket at your word.”

He would delay no further. At the distance the Bah-Sangah priests had insisted on incorporating into every aircanoe’s design, the brass pipe wrapping the earth-fueled engine must surely be glowing with readiness. Beads of water would be evaporating off of it like sweat in a desert.

The lever releasing the engine’s steam into its turbine chamber fitted smoothly between his hands. He pressed it flat against the hull wall. A slow surge forward began; Tink let it rock him to his feet. But he stayed at the controls, his back to their destination. The heavy rain wiped away the distances normally revealed to him by his keen sight, and did the same to a lesser degree to his sense of smell. His hearing, however, had increased. He untied the ribbons holding shut the louvres set between the aft windows. He let the sound enter him. Below, above, around the engine’s vibrant thrum the rain’s echoing bounces told him of the changing shape of the landscape.

The glad dampness of leaves outsang the stoic stones and placid clay tiles of buildings. This was a neighborhood of several inns, as he recalled, each with its stables and gardens. Patient wooden sheds used as storehouses lined a strip of dull, packed earth—a road. It ran a long way behind them but not far ahead, so Xu Mu had reached its end.

In his last clear look before the rain Tink had seen that this road led to the temple’s cemetery. He guided the aircanoe past the graveyard’s iron gates and found the headstones’ slight, isolated pretensions to endurance gently funny.

Longer intervals in the raindrops’ echoes indicated a slope downward to starboard, which in turn gave way to the pattering surface of a pond. Next came the temple’s rear courtyard: cobbles packed tightly together around a high prominence, most likely a large devotional image. Just beyond loomed the temple itself—the “church” they called it—facing west, toward Europe, toward the architecture it mimicked with its “gothic” arches and colored windows and tall towers filled with bells of iron.

CLANG! CLANG! CLANG! Who dared to ring the temple bells? The chiming came from the closest of the twin towers. Its clamor ceased and he heard the soldiers in the relative quiet, swearing and panting and smacking their sandals on the tower’s winding stairs, higher and higher. Then Bee-Lung’s gleeful cackle and her scent! All their scents—the clouds did no more than drizzle now, and first smell then sight returned. The low, pierced wall surrounding the nearest tower’s roof appeared; it was at his level. Would they hit it?

No. Dark blurs streaked past the pod windows and struck the ground. Xu Mu leapt in the air. The crew had dropped sandbags. Tink stood and ran to the control levers. He fell twice: the change in altitude. Even so little. He shunted the steam off the turbine. Of course this didn’t stop them moving, only slowed them down. Soon they’d be past— But there went the cargo basket, whirling away as fast as the workers could unwind it.

And there were his sister and kin, emerging from a hatch in the green copper roofing. Too late, though: the basket dangled now over the church’s broad front steps.

They must go back. Turning was easier this time. He used Xu Mu’s forward momentum to execute a tight circle, and made the second attempt as the last of their kinetic energy bled away. The alignment was perfect. They hovered in position.

Soon he heard Raghu’s joyous shouts of relief, the Chens’ ribald jokes at the expense of the men working the winch, Bee-Lung’s loud laughter, Kwangmi’s silence. Kwangmi came down the pod’s ladder and without comment took her usual spot. Tink got up from the bench to give it to her.

Then he shook his head and sat back beside her. “No.”

“No?”

He shook his head again. “No. You are as sure as I am of where we’re going. Take the observation post. Direct me.”

Excerpted from Kinning, copyright © 2024 by Nisi Shawl.